The Michael Principle

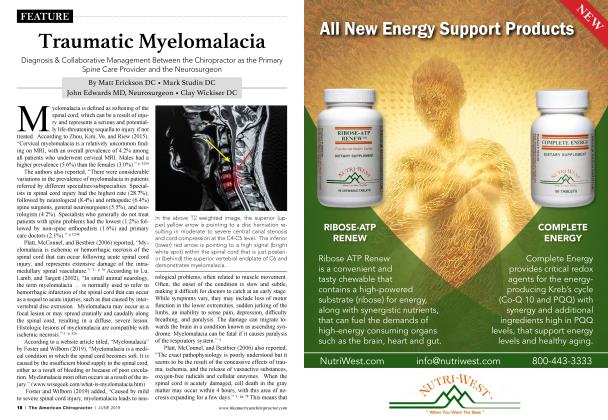

FEATURE

PROPRIOCEPTION

Body Sway, Proprioception and Spinal Curves; Part 3

Richard M. Opper DC

Michael was 8 years old when his mother brought him to the office because he was walking and running on his toes (lordotic gait); it was 1986, and the diagnosis was Duchene's Muscular Dystrophy (DMD). He was treated occasionally until he died in 2015. By then he had earned an engineering degree and was an aeronautical environmental design engineer. He married and became a father.

When Michael was 12 years old, he was confined to a wheelchair due to encroaching and profound muscle weakness and the inability to maintain upright balance caused by biomechanical failure of the pelvis. It is the imbalance that, in turn, causes the characteristic lordotic gait observed in children with DMD. When rapid femoral growth begins in adolescence, they are unable to stand as the imbalance worsens and they must use a wheelchair, which is when a markedly progressive scoliosis appears.

The male prevalence in DMD is due to a genetic mutation and the female specificity in AIS is due to the dimorphic pelvis, which is prone to high pelvic incidence in approximately 2.5-4% of girls, annually, at the onset of adolescence (Stylianides GA, 2013). The mechanics of the scoliotic process are identical in both conditions despite the more severe distortion in DMD. It has been reported that the degree of Cobb’s angle in AIS is proportionate to the degree of the lumbar lordosis during the early progression stages (Van Hanswyck E, 1978). The excessive lumbar lordosis seen in AIS is a manifestation of pelvic tilt (high pelvic incidence). Although not acknowledged as such, the scoliosis present in children with DMD is also an adolescent idiopathic scoliosis.

The common characteristics are:

1. Age at onset (adolescence)

2. High pelvic incidence

3. Rapid femoral growth

4. Disequilibrium (standing unbalance

5. Lumbar hyper-lordosis

6. Right-sided major curvature

7. Both are idiopathic.

Michael, too, developed a scoliosis while in his wheelchair, which progressed with time. He was offered surgery to straighten it but Michael refused. Despite the consideration of high-risk surgery, he had learned to make himself more comfortable while sitting by having his legs crossed in the Lotus position. Apparently, by elevating the femurs in that manner and considering that there were strictures that limited the motion of the femoral heads, he was able to rotate his pelvis backward, which, in turn, straightened his spine and enabled him to sit comfortably. Coincidently, in the early 1980s and again in the late 1990s, orthopedic surgeons who had been unsuccessful at preventing and reducing thoracic curve progression with instrumentation fusion for scoliosis in children with DMD discovered that when they extended the instrumentation to the pelvis, which leveled sagittal tilt and obliquity, that curve progression ceased and Cobb’s angles were substantially decreased (Alman BA, 1999). This protocol is in use today in children with DMD who have severe curvatures. The principle is that a level pelvis is necessary to stabilize the spine above.

Understanding this biomechanical principle, which facilitates successful surgery on severe scoliosis in children with DMD, one might assume that it would have implications for treatment of healthy children with idscoliosis, which might resolve curve progression and reduce curve angles. Unfortunately, nonsurgical therapies such as bracing, physical therapy, chiropractic and exercise therapy have had only poor or marginal outcomes. These therapies have traditionally been focused on the frontal plane distortion; that is, the lateral curvatures. It is easy to understand because of the dramatic appearance of the thoracic curvature and the attendant rib hump. It has been obvious that pushing against these progressive curves with orthoses or manipulations or traction is mostly unsuccessful. It is usually the very mild curves that respond the best to these procedures and even then complete resolution almost never occurs. It may be that we have been treating the scar and not the wound.

Leveling the pelvis will resolve progressing scoliosis with related unbalance in children with Duchene’s Muscular Dystrophy or Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis

Thoracic curve progression, in healthy children with AIS, ceases of its own accord usually between ages 14 and 15 in untreated cases. What occurs is that the tilted pelvis (high PI) is made level naturally by the flattening curves in the sagittal plane (Roaf, 1966). It is as if the body has performed its own fixation surgery to rotate the pelvic backward to reduce the sacral angle and lumbar lordosis, and stabilize the spine. The other characteristic of the idiopathic scoliosis is that disequilibrium stops precisely when the lateral curve progression ceases (Yamamotto, 1984). The reason why this natural process described above does not resolve the progressive scoliosis and imbalance in children with DMD is due to the progressive and profound muscle weakness that precludes a successful outcome, which necessitates spinal surgery to prevent cardio-pulmonary compromise, as well as to enable sitting in a wheelchair (Moes CCM, 1998). Surgery is the only option for children with DMD, except for a few like Michael, who learn to position themselves so that the pelvis rocks backward and straightens their spine and those whose pelvic obliquity is less than 10 degrees (Alman BA, 1999). The tragedy is that with DMD every muscle disappears, whereas in AIS the musculature remains healthy. The “righting reflex,” (neuromuscular spinal reflex) directed by the spinal column complex proprioceptors is evidenced in both AIS and DND spinal deformities as a powerful response to standing imbalance caused by exaggerated pelvic incidence. The standing imbalance is resolved in untreated AIS in about 60 months from onset when the sagittal spinal contour levers the pelvis back to a normal PI.

Force plate analysis using COM tracking software produces linear graphs that visualize the movements of the COM while standing erect. These devices, like the BtrackS Balance Plate System, can be used for AIS screening to quantify standing imbalance, which may precede the formation of a thoracic scoliosis in adolescent children. The graphs illustrate how the proprioceptive receptors in the spinal column and head react to imbalance. When a graph line is moving away from the center the indication is that the body is about to fall down and, when the line returns to the center, it indicates that the proprioceptors have signaled the brain to contract deep spinal muscles to pull the body back to a balance point, which is the COM over the center of the body’s base of support. With AIS this process continues until the offending PI is reduced; but, in DMD, the proprioceptors fire normally but the musculature will not respond adequately and by about age 12 they fall down.

Chiropractic science and methodologies are uniquely appropriate for diagnosis and care of AIS. Diagnosis must be early, preferably prior to curve formation and, optimally, within two years of onset. Differential diagnosis is crucial as numerous other pathologies can cause scoliosis; if one is unsure, a pediatric neurological consult and x-rays are advised. Force plate technology is an accurate predictive and takes only a few minutes to perform. Follow-up scans will produce objective measurements of body sway, which have shown to be more pronounced during the early stages of progression when the curves are smaller and less intense than in the later stages when the Cobb angles are larger (Gregoric M, 1981; Sahlstrand T, 1978), which is one of several reasons to be proactive with treatment from the onset rather than just observational for the first 24 months as is the medical model. The objective of treatment is to restore the pelvis to a neutral pelvic incidence until bone growth stops. An innovative brace that neutralizes pelvic incidence will stop curve progression by eliminating standing imbalance and will likely resolve 3D spinal distortion. The chiropractor must ensure frontal plane leveling (obliquity) and resolve leg length discrepancy on a weekly timetable until femoral growth ceases or until body sway measures are unremarkable. Femoral growth may continue for 60 months and is a major contributor to high pelvic incidence in the adolescent female pelvis (Zahn RK, 2016 Aug). Although spinal surgery is performed on only .01% of children with AIS, 99.99% must live with the condition their entire lives with that knowledge and the consequences of curve progression into adulthood.

The Michael Principle, has been proven to be valid by orthopedic surgeons who operate on children with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis who have Duchenne muscular dystrophy. When this principle is applied early on with non-surgical protocols, to healthy children with AIS, millions of kids may never have to experience a lifetime of disfigurement and pain. Thank you, Michael.

Michael can be seen on YouTube at “Michael Degnan: My Journey of Faith. ”

Dr. Opper is a 1969 graduate of The Columbia Institute of Chiropractic, Partner in Palmer Chiropractic PC, Palmer, Mass. Authored: "Paradoxical Motion of The Cervical Spine...." JACA, Jan, 2000; Article under review: "Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis is an Etiotropic Remodeling of The Spine in Response to Disequilibrium". [email protected]

References

1. Atman BA, K. H. (1999). Pelvic obliquity after fusion of the spine in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Bone and Joint Surg, 821-24.

2. Gregoric M, P. F. (1981). Postural Control in Scoliosis. A statokinesimetric. ACTA Orthopaedica Scandinavica, 59-63.

3. Moes CCM. (1998). Measuring The Tilt of the Pelvis. Ergonomics, 1821-1831.

4. Roaf. (1966). The Basic Anatomy of Scoliosis. J Bone and Joint Surg, 786-792.

5. Sahlstrand T, O. R. (1978). Postural Equilibrium in Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis. ACTA Orthopaedica Scandinavica, 354-365.

6. Stylianides GA, D. G. 2013. Pelvic Morphology, Body Posture and Standing Unbalance.

7. Van Hanswyck E, B. W. (1978). www.oandplibrary. org/op 1978 02 7.asp?mode=print. Retrieved Jan 30, 2018, from oandplibrary.org.

8. Yamamotto, K. E. (1984). Etiology of Idiopathuc Scoliosis. J Jpn Orthop, 54-57.

9. Zahn RK, G. S. (2016 Aug). Pelvic tilt compensates for increased acetabular ant eversion. Int Ortho, 1571-1575.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue